As part of the #Dungeon23 challenge, I plan to create a megadungeon starting in March. January and February are planned as hexcrawls to the actual megadungeon, the Lost City of Kyrthar Tahlketh. This split gives me a chance to think about the design of the dungeon.

The first problem I want to address is not which rooms there should be, or what the leitmotif of each level of the dungeon should be, or what monsters, NPCs, factions, traps and treasures I should fill the rooms with, but something much more basic:

How do I need to structure, build and describe a dungeon so that it is easily playable for the GM and the players?

My first D&D campaign

My first campaign as a D&D player was „The Lost Mine of Phandelver“, and that was my first contact with a large dungeon:

The Wave Echo Cave ( https://prints.mikeschley.com/p856083253/h349521AA ).

The Wave Echo Cave is not a mega dungeon. It has only one level.

And our inexperienced DM (it was also his first campaign) had great difficulty describing the dungeon to us as we explored it. This inexperience in describing the dungeon met with the inexperience of us players, who had no idea how to map a dungeon.

It has to be said that we played at a table and the DM didn’t just put the map in front of us. That’s usually the best way to explore a dungeon. The characters didn’t have a map, so the players shouldn’t see one. If they want one, they have to make one themselves based on what they see (i.e. the GM’s description).

Now, Wave Echo Cave is not an easy cave to describe. I am sure that even experienced GMs would have problems explaining the cave, especially area 2, in a way that would keep the players engaged and not have them fall asleep. The map looks good in the overview, but it’s not easy to describe, which is why we players eventually gave up trying to map it, and the GM more or less just told us where to go so we wouldn’t get lost.

So I want to look at what a dungeon needs to have to be playable at all.

What design goals should a dungeon have?

The following design goals apply to a tabletop or online game in which the GM does not reveal all or part of the dungeon map to the players during exploration. Why this restriction?

In my opinion, exploring a dungeon without a map for characters to move their tokens around is the most immersive way to explore a dungeon. The overhead view of a map makes it more like a (computer) game. You are no longer imagining yourself as a character, but as a player looking at how best to move your pieces. The best way to explore a dungeon is with Theatre of the Mind. In my opinion, non-in-game maps have no place in the game except as battle maps (and only if you really need them). They are there for the GM to guide the game, not for the players‘ eyes. If you give them to the players, you are giving them a bird’s eye view, you are taking them out of their character’s perspective and out of the world.

Now let’s move on to the design goals:

- The dungeon should be easy for the GM to describe.

- The dungeon should be easy for the players to navigate.

- The description should draw the players into the game, i.e. give them a sense of the game that matches the dungeon.

What does that mean?

We need to design our dungeon so that the GM can quickly and easily give the players the key information they need to navigate. Things that we automatically pick up when we enter a room need to be immediately obvious to the GM, so that she can describe it to the players in a way that they can find their way around as easily as if they were standing in the dungeon themselves. The description also needs to convey the feel of the game that we want. Is it a tight, oppressive dungeon? Is the danger great? Is it a place of refuge?

To make the dungeon easy to describe and navigate, it must not be too complex.

So let’s look at some design principles to help us build the dungeon.

Design Principles

Principle 1: Each room has a maximum of 6 entrances and exits. One for each point of the compass, and one up and one down. Ideally no more than 4 entrances and exits.

An example of the application of this principle:

You enter a large round room from the south. There is a fountain in the centre, which gurgles softly, adding a pleasant humid coolness to the otherwise hot and dry air of this cave. To the north, another tunnel leads deeper into the cave, and to the west, a narrow passage seems to lead slightly upwards.

An example if you do not follow the principle:

Enter the large round room from the southwest. In the middle of the room is a fountain that gurgles softly, adding a pleasant, humid coolness to the otherwise hot and dry air of this cave. There are more passages to the north-west, north and north-east of the cave, 4 to the west and 2 to the east. Next to the passage you came from, there are two more passages to the left and right….

Example 1 is easier and does not overtax the players. When two or more entrances/exits point are in the same direction, questions arise as to how many degrees they deviate from each other, how far they are from each other, and so on.

When drawing a map, it makes a difference whether the north-west corridor actually points directly to the north-west, or perhaps to the north-north-west, or more to the north-west-west, or perhaps simply directly to the north, and it is only located in the north-west corner of the room …

The first example is much clearer and leads to fewer questions about the layout. Players know immediately where to go and can concentrate on the important things, like exploring the room. The principle simplifies the dungeon design to such an extent that players will be grateful, because they can follow the descriptions more easily and make conscious decisions more easily. In this case, reduction makes the game more fun.

Exceptions: Rooms within rooms. A prison, for example, consists of a room with many cells, and therefore many exits, or an apartment building with many flats, and there is a corridor with many doors leading to the flats. That’s fine, of course. But the individual cells should not all have additional exits, for example. This would make the map again too complex for the players.

Principle 2: The approximate size of the room is sufficient for the description. Players do not need to take measurements.

Example of this principle:

You follow the corridor to the west and come to a small cave that you can squeeze into with some difficulty. There are no other exits. At the end of the room is a small chest.

What happens if you don’t?

You follow the passage to the west and you will come to a cave that is 10 feet wide and 15 feet deep. At the end of the cave is a small crate. There are no other exits.

Both give the players enough information to navigate, but the direct measurements destroy the feel of the game (if the characters don’t pull out a tape measure, how are they supposed to know exactly how wide and deep the cave is?) Is the cave square if it is 10 by 15 feet? Is it oval? Exact measurements encourage geometric shapes in the mind, which then have to be painstakingly broken down:

The irregular cave is 10 metres wide at its widest point, 15 metres deep at its deepest point…

It immediately becomes more complicated. It becomes simpler if you do not give specific sizes, as in example 1. Where possible, sizes should always be related to each other. The easiest way to imagine this is as follows.

The passage is wide enough for two of you to walk side by side, rather than 10 feet wide.

The ceiling of the cave is so high that you cannot see it in the light of the torches is better than the ceiling being 50 feet high.

I can’t really think of an exception right now. Except perhaps that the player characters are part of a survey team?

Principle 3: Every room needs a distinctive feature.

If all rooms look and feel the same, it will be harder for players to find their way around.

„The room with the big fountain“ is memorable. „The 20 x 20 foot room“ after a „15 x 15 foot room that comes after a 20 x 15 foot room“ has no real recognition value.

Exception: if you deliberately want the rooms to all feel the same, you can break the principle. But if you don’t, stick to it and give each room, or most rooms, something unique.

Principle 4: Information before feel.

Example, well:

You enter a large, round room from the south. There is a fountain in the centre, gurgling softly and adding a pleasant, humid coolness to the otherwise hot and dry air of this cave. To the north is another tunnel that leads deeper into the cave, and to the west is a narrow passage that seems to lead slightly upwards.

Bad example:

You enter the large circular room through the southern entrance and are immediately struck by its beauty and grandeur. The room is dominated by a stunning fountain in the centre, its water flowing from an intricately carved statue of a mythical creature. The splashing of the water fills the air with a pleasant, humid coolness that distracts from the oppressive heat and dryness of the rest of the cave.

The walls of the room are decorated with impressive reliefs and carvings depicting scenes from times long past. You can tell that this place was once a temple or place of worship and you can feel the spiritual energy still in the air. The floor beneath your feet is smooth, dark stone that shimmers in the light from the fountain.

To the north of the room is another tunnel that leads deeper into the cave. A cool wind blows from it, bringing the smell of damp stone and mould to your nostrils. It is as if the darkness of the tunnel invites a new challenge.

On the west side of the room, a narrow passage leads slightly upwards. A faint glow of light can be seen at the end of the passage. It may lead to a viewing platform or another room with an impressive view of the surroundings. The passage itself is lined with old, weathered paintings and inscriptions that tell of times long past.

Return to the fountain in the centre of the room: the water flowing from the statue is so clear that you can see the bottom of the fountain. You can see that the water comes from a natural spring and has travelled through a labyrinth of underground caves and passages. The edges of the fountain are covered with green plants and moss that benefit from the moisture. You can even see some fish swimming in the depths of the fountain, feeding on insects that fall into the water.

A particular highlight of the fountain is the elaborate statue in the centre. You can see that it is made of gleaming marble and that every line and contour has been carefully crafted to create a perfect image of the mythical being. The statue’s eyes seem to be alive and watching you, as if it were a guardian of the well and the room.

All in all, the large circular room with the fountain in the centre is an impressive place full of beauty and mystery that will captivate you.

To exaggerate, such a description as the first one given upon entering the room would overwhelm players. Such a wealth of detail is too much. Finding the right balance between gameplay and information is always a balancing act, but especially in the beginning, you should always err on the side of giving the most important information and make it shorter rather than longer.

The exceptions: The really important rooms, which have something in them that should really overwhelm the player when they see it.

But then you should repeat the most important information briefly at the end, so that the players have a chance to process it.

Repetition is the mother of information management. It allows the importance of information to be weighted: Unimportant details are mentioned once, important things twice and the most important things, such as the main element of the room and where the exits are, three times.

Principle 5: Intersections and turns in corridors should be treated as rooms.

If corridors meander, turn, or even end at junctions and are not treated as rooms, players can quickly become disoriented. If you don’t want this to happen, treat all crossroads and junctions like rooms. This means adding a short description of the possible paths and, ideally, a design element that has some recognition value.

Principle 6: If there are multiple paths to choose from, players should have enough information to not make a completely random choice.

Good example:

You are standing in front of two doors. On the left door is written in elven script „Here awaits certain death, but also great treasures“, on the right door is written in dwarven script „Here awaits eternal life, enter with humility and leave your worldly things behind“. Which door will you take?

Bad example:

You are faced with two doors. One leads to the left. The other to the right. Which one do you take?

If the players have no idea what is behind which door, they will make completely random decisions. Therefore, the players should always have or be given clues as to what might be in this or that direction. The clues may turn out to be wrong later, but they should not make decisions in an information vacuum. You can do this a few times, but if it happens too often, the game becomes uninteresting.

When do you use these principles?

These principles are useful when building large dungeons. The smaller the dungeon, the more you can deviate from them. In a dungeon with only ten rooms, it’s not so bad if you get lost and lose your bearings, because you can quickly find your way back. But in a mega-dungeon with dozens or even hundreds of rooms, you need to be more careful to make it a fun experience for the players.

Example of building a dungeon

So how do we build a dungeon using these principles?

We start with a simple concept drawing to give the GM an overview. In the beginning, we focus on the structure and not so much on the content. We keep it as simple as possible:

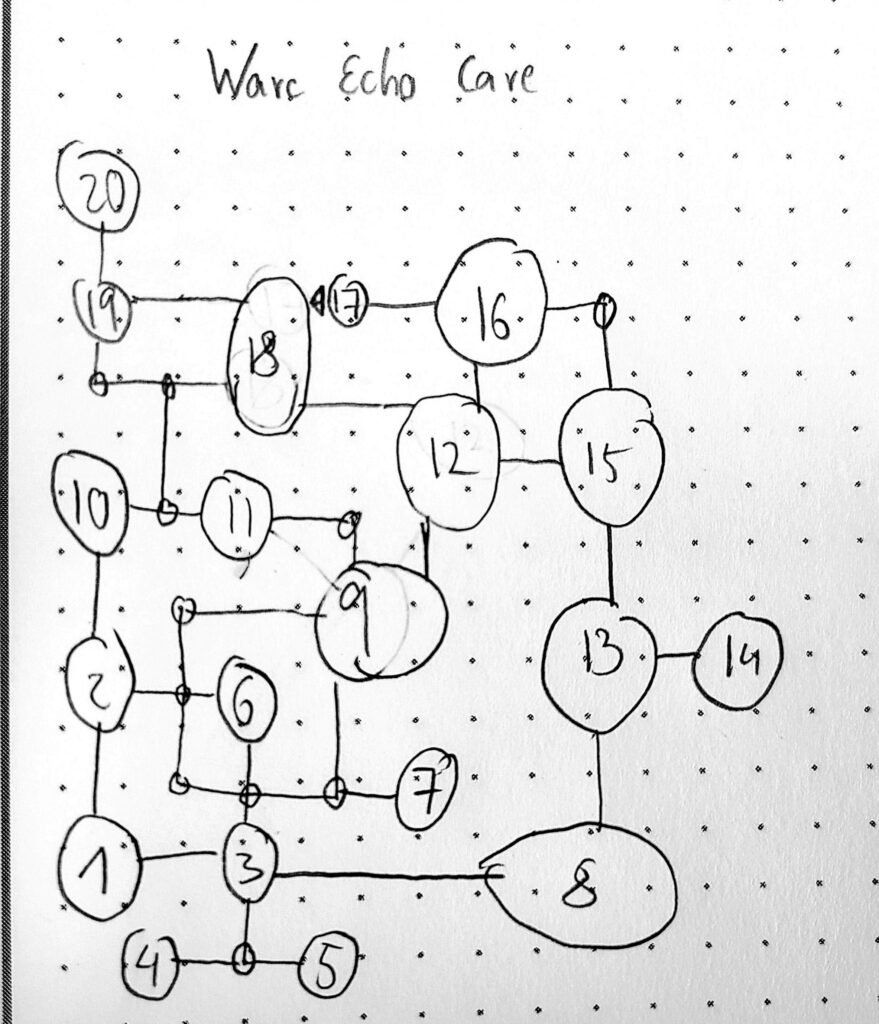

This is a relatively complex dungeon structure that the players:inside can still navigate and that the GM can describe as simply as possible. Each circle represents a choice or change of direction for the players.

At a glance, the GM can see which paths the characters can take, where they need to look for hidden paths, or where they need keys or other ways to move forward. Such a simplified diagram is a great tool for any GM. And if, for example, you want to use a dungeon from a published adventure, it is very helpful to write it down in this format and reduce it to its bare essentials.

Let’s take our Phandelver map from Wave Echo Cave ( https://prints.mikeschley.com/p856083253/h349521AA#h349521aa ) and convert it to the above format:

And we immediately see that it becomes much clearer for us. We can also see that there are a lot of bends and curves that we need to take into account so that we and our players don’t get frustrated when we have problems navigating Wave Echo Cave. Basically, all the unnumbered circles are problem areas that we should take into account when preparing, and it also shows that the basic structure of Wave Echo Cave was not quite optimal, especially for inexperienced players and GMs, because in the map key defacto 10 rooms (all the unnumbered circles) are missing and have no description, but these need to be described to the players by the DM so that they do not have problems with navigation. But thanks to the diagram, we can now see why we had so much trouble navigating the cave in my first campaign.

So with this simple structure, you can break down any dungeon or location you want your players to explore and check it for playability at a structural level.

In the next article on dungeon design, we will look at how we can now bring our examplatory dungeon-diagram to life and create a dungeon that feels real.

If you have any suggestions, ideas or questions, please feel free to leave a comment.

To make sure you don’t miss a thing, you can follow me on Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon or Twitter or suscribe to the RSS Feed.

Yours truly, A.B. Funing